I said I might return to reviewing media for the blog once Jailbird Nocturne was done, and that’s turning out to be the case! Neat.

When I started writing these reviews a year and a half ago, I mentioned that I was a time in my life when I was especially interested in stories about queer women, and not only has that persisted, but the past 6 months have treated me to some really good stories of the sort. My recommendations have always skewed towards the gay side, but this is by far the most trans-centric list of recommendations to date.

These are also the most horror-tinged set of recommendations that I’ve given so far. I’m not normally a horror fan, but given the tight-knit relationship between horror and queerness, taking a turn into spooksville was unavoidable in my quest for good queer fiction. That said, among my recommendations, visual novel We Know the Devil and film I Saw the TV Glow are horror-adjacent, but I don’t think either is super scary - if you, like me, aren't a horror junkie, you should find them accessible. WKTD plays with horror tropes and aesthetics but was moving for other reasons, and I found TV Glow to be unsettling at worst – I watched it in a dark room by myself at night and was able to sleep just fine afterwards.

I can’t say the same of the novel Brainwyrms, which is straight-up terrifying. The manga Wandering Son is the only horror-free offering this time around, unless you consider being a closeted trans kid in the aughts to be inherently frightening (fair, honestly). Let's start there!

Wandering Son (Takako Shimura 2002-2013)

Wandering Son is a manga that follows two children, “a boy who wants to be a girl,” and “a girl who wants to be a boy,” from late elementary school to the end of high school in the 2000’s. It has a reputation as being the quintessential trans manga, mostly from a lack of competition during the time it was serialized (the decade that immediately preceded the “transgender tipping point”).

A lot has been said about Wandering Son’s failures. The series' handling of Yoshino, the series’ deuteragonist and only transmasc character, is, by the end, clumsy at best*, and trans woman Yuki's introduction as a sexual predator is, um, not great. But! For a manga written by a cis woman in the 2000’s, I’m far more amazed by how well the author understands the interiority of closeted trans children. I remember a scene where Shu and Makoto – two closeted trans girls – had a hard conversation about how their voices were on the cusp of changing for the worse. It immediately reminded of what it felt like in health class at age 10 when the changes that male puberty would bring were explicitly spelled out to me for the first time and I was filled with absolute dread. I’ve never seen that dread represented in a piece of media before. Wandering Son's trans characters may not always be realistic, but I do find them to be genuinely relatable in a way that very few cisgender writers are able to make them.

Before Wandering Son, the only other story I had read about a transgender child was Laurie Frankel’s This Is How It Always Is, a 2017 novel about a young trans kid and their mother that was inspired by the author’s own parental experience. It was a good book, but it was a story that felt mostly foreign to me. It told the story of a kid who was able to identify as transgender at a young age and receive parental support in their social transition, an experience that felt more typical of the experiences of trans youth in the mid-to-late 2010’s, not the 2000’s. By comparison, as a late-ish millennial, the word “transgender” didn’t enter my vocabulary until my late teens. I didn’t have the language to make sense of my gender dysphoria, let alone begin the work of coming out to myself, let alone undergo a social transition, with or without parental support, until adulthood.

I think what makes Wandering Son so special is in how dated it is. The young trans protagonists of the story are able to vaguely relate their experiences to adult “transsexuals,” but they are otherwise uncertain about what their desires to be a different gender mean. Their friends see their transsexual desire as anomalous quirks, not part of a broader, common phenomenon. Their parents don’t know how to make sense of their children’s transness. Wandering Son is sometimes criticized for being a story with “bad” trans representation, a story where people struggle to identify, let alone support, their trans family and friends, where youth give up on their cross-gender ideations and submit to life as their birth sex, where the possibility of medical transition is barely whispered. But that is what being a closeted trans kid was like back then! It was a period of invisibility, isolation, and confusion.

I don't mean to be dismissive of the current condition of trans youth - health care bans make it a brutal time to be out as a trans kid in the US - but we have at least irreversably passed into a new era of visibility where stories about trans childhood prior to the 2010’s, which were already rare enough, will only become increasingly rare and irrelevant to younger generations. This is a good change, but it makes it hard to find narratives from which I can make sense of my own childhood. Wandering Son is imperfect, but it bears the burden of being one of the few popular stories that portrays the specific era of trans childhood that I experienced, and for that, I am grateful.

I don’t mean for my discussion of Wandering Son to be entirely hung up on its representation – I am recommending it as well for its character drama and lovely art (those rare watercolor pages are gorgeous!). The series received an incomplete English translation, so enjoying the entire series will require you to find (passable enough) fan translations online.

I could probably write a whole separate essay just about Yuki. Maybe another time. Moving on!

*SPOILER: For those who've read Wandering Son, I feel like I need to clarify my position regarding Yoshino: my interpretation of the ending is that Yoshino loses her nerve to transition and NOT that her desire to be a boy was "just a phase" (and I am only using feminine pronouns for her because that is how she self-identifies by the end of the story and her true gender is, frustratingly, canonically vague). Not only do I think this interpretation is supported by the text, but I just like it more for, y'know, being the not transphobic interpretation. However, I don't know if that was Shimura's intention. I think that she leaves things waaaaay too ambiguous here, and it is disappointing that the only transmasc character in the manga gets the "bad ending," especially given how underrepresented trans men and boys have been in fiction. Yoshino deserved better.

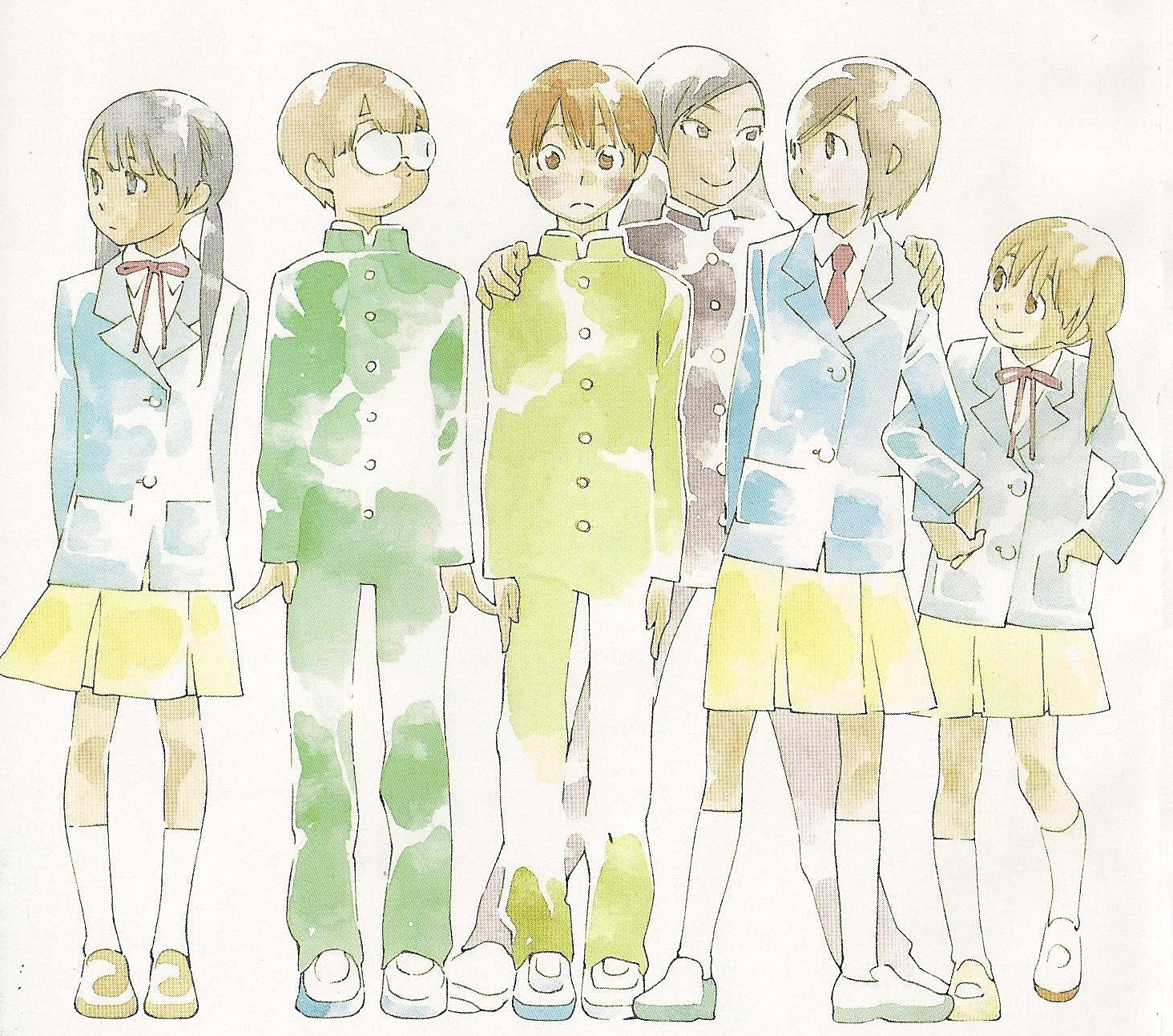

I Saw the TV Glow (dir. Jane Schoenbrun 2024)

If Wandering Son was the first time I saw my closeted trans teen self represented in a piece of media, then I Saw the TV Glow was the second.

It’s a psychological horror film about two teens who really like a campy television show and slowly begin to question reality. Excellently shot, written, and scored, it’s the sort of movie that reminded me that movies can be good, actually. I am the internet’s best film critic.

The trans representation here is metaphorical rather than literal, although explaining the metaphor would spoil the plot of the film. Distilling the experience of gender dysphoria into an allegory gives it a certain universality that could not be achieved by the more literal depictions of transness in the rest of this blog post – I think it was a brilliant decision.

Sometimes cis people ask me what gender dysphoria feels like. I'm never sure how to answer - I think there's a misunderstanding that gender dysphoria is a singular feeling and not a condition that can ellicit so many different thoughts and emotions. So it's nice to have a movie I can instead point to and say "that. It felt like that. The Midnight Realm is real, and I used to live there."

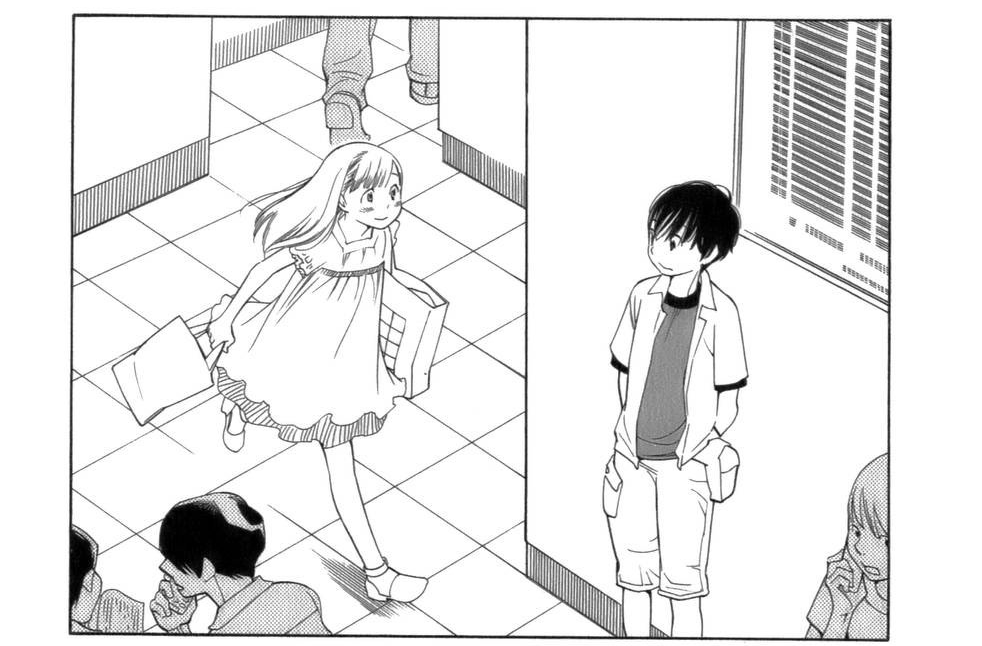

Brainwyrms (Alison Rumfitt 2023)

If I Saw the TV Glow is a metaphor for gender dysphoria, Brainwyrms is a metaphor for transphobia. It’s a horror novel about parasitic Lovecraftian brainworms that turn British people into TERFs. At least, I’m pretty sure it is? I’m a little fuzzy on the particulars of how the worms work – it’s left purposefully vague.

It’s brutal and filthy and feels unsettingly familiar. Yes, the monster in this story is a parasite that spreads from person to person and turns them into a violent, cruel, abjectifying transphobes, but if you remove the worms and the sex cult, you’re just left with the story of a trans woman navigating a world that hates her only a smidge more than the real one. The horror in this story largely cumulates into the sort of transphobic hate crimes that are reminiscent of the ones that actually occur. Connections to this current moment in trans politics aside, the novel’s use of literal brainworms as a metaphor for the spread of bigotry has a timeless universal relevance to it that I think most readers would find haunting.

I had a good time with it. I am the internet's best book critic.

We Know the Devil (Worst Girls Games/Pillowfight Games 2015)

also Heaven Will be Mine (2018).

There’s room for three in my world, and only two in his.

I felt like I had a pretty good streak going of cleverly connecting each prior entry in this list to the next, but I'm not sure how else to transition into this review except just to say that I absolutely loved We Know the Devil.

WKTD is a horror-tinged visual novel about three queer teens sent to a Christian summer camp for supposedly “bad” kids where attendees are regularly made to spend the night in a remote cabin in the woods to confront the literal devil. It’s the last week of camp, and it is finally time for our three protagonists to undergo this supernatural hazing. “Don’t worry guys,” one of them reassures the others, “I hear hardly anyone ever dies.”

Over the course of each playthrough, the player is forced to make choices about which pair of characters in the trio will participate in each scene, meaning that one character must always be excluded. The character who is excluded the most by the story’s climax is the one who lets the devil into them and, consequently, must be exorcised by the other two. Or was the devil always inside of them? Is it possible to get through the night without any of these poor kids getting scapegoated?

Speaking of our protagonists- God, I just love them so, so much. WKTD’s writing is absolutely stellar, with subtle characterization and worldbuilding. It’s a thematically rich story about the queerness, shame, moralization, and social exclusion that struck a nerve with me as a queer who still struggles with the misguided impulse to “be one of the good ones,” whatever the hell that means. Phenomenal artwork and an unsettling soundtrack sell both the story’s more humorous and dramatic moments.

It is worth playing through the game four times to experience each ending – the game’s true ending doesn’t hit as hard if you haven’t read the other three, and those three are, uh, not the true ones. I am the internet's best games critic. Each playthrough is just an hour long, and the script is sufficiently enjoyable and packed with enough subtle details that I had a great time rereading it. This is a visual novel that was properly written to be enjoyably replayed.

I finished my playthrough of the game four days before writing this draft and have not been able to stop thinking about it since. WKTD is easily one of the best visual novels I have had the pleasure of experiencing. I was originally planning on writing about Heaven Will Be Mine, Worst Girls Games’ fantastic follow-up about space lesbians in giant robot suits, but We Know the Devil hit me even harder. I still recommend both.

That’s all for now! I was also planning on writing about Alice Stoehr’s most recent short story collection, Less + Worse Forever, but I already wrote about her first three collections and don’t want to retread old territory.

In other news, I’ve finally locked my Twitter account for good. Do follow me on Bluesky for when I start posting games updates again! I’m taking a break from game dev to focus on music and health-related stuff, but I look forward to resuming work on the Cardinger sequel once my other affairs are in order.

Since I last wrote, I’ve made a trailer for Jailbird Nocturne (better late than never!) and have arranged for a physical version to be sold on the Pizza Pranks Tape Market! Thank you so, so much to everyone who’s donated to the game or bought the physical release – I’m amazed by the interest and support. If you’ve finished the game, don’t forget to leave a rating or a comment on the itch page, or just tell me what you thought by any other method! It means a lot.

Finally, as of a couple of months ago, Cardinger is now available for free in print and play form! I’ve been meaning to make .pdfs of the cards available for a long time – thank you to the kind online stranger who nudged me into finally making it happen.