On March 20th, I made an appearance on the 18th episode of Indiepocalypse Radio following my feature in the game bundle zine Indiepocalypse #14. I appeared in a one-on-one segment with Andrew, the host, and a separate segment with the other two guests, Phoebe and Adrian of the Black Lavender team.

The recording of the episode itself is unedited, meaning that the episode contains a lot of casual chatter that may or may not be enjoyable to the average listener, but I greatly enjoyed being on the program, and I wanted to share it regardless. So, I've edited down the conversation to what I think are the most personally relevant bits to me and my work and transcribed it here.

On Glorious Trainwrecks, Craftsmanship, and Iterative Game Sketching

[After introductions and the initial ice breaking, I make a reference to my loose connection to the Glorious Trainwrecks game developer community, which is focused on the purposeful creation of games with low production value.]

Andrew: Oh! Oooh, do you mind the Glorious Trainwrecks circle too? How exciting!

Alex: I mean, I'm not as deep as some are. I think I've submitted to five of their jams. It's a funny thing where, actually, speaking of Baltimore, when I… so, full life story: I grew up in and around Baltimore -

Andrew: No, no, Alex, full life story. You were born...

Alex: Okay, here we go… I went back to Baltimore for a few years [after college] while I was figuring my life out, and a venue, the Windup Space (which is closed now, sadly) used to have a board game night... I met somebody there, and neither of us knew that we made games or anything (it was my friend Stephen, if anybody knows him online as let-off-studios, that's who it was)! So, we friended each other on Facebook, and then he just posted about a game jam he was hosting on Glorious Trainwrecks. I was like, “Oh! I make games by the way!” “Oh, really? Shit.” And that's how I started submitting to those jams.

Andrew: Glorious Trainwrecks is a beautiful thing, I think. I love busted-ass stuff that is trying something, you know?

Alex: Yeah, and even nowadays, I'm trying to do stuff that's a little more polished, but it's still very dear – they have a very dear mission [to me], and there are so many people there who I respect who just make just fantastic art.

Andrew: The person can leave the trainwreck, but you can never take the trainwreck out of you, you know?

Alex: Ha ha! Oh man…

Andrew: I think that's the spirit. As long as I think the spirit of wanting to not necessarily worry too much about… I think there's a difference between "polish" and "safe," you know?

Alex: Yeah, and I think that even when I think about some of the more explicitly trash game-y or trainwreck-y stuff I've made, there's usually something that's hyper-polished in there. There's still craft that's applied, and even with an aesthetic like the trainwreck aesthetic itself, you have to know what you're doing to make something that, with hastily drawn Microsoft Paint art, is still readable and visually compelling.

One of my Glorious Trainwreck jam submissions, Clark Stanley's Van Racer

Andrew: Yeah, I've played a lot of non-glorious trainwrecks, I guess you would call them -

Alex: - Sure. Inglorious trainwrecks -

Andrew: - as games that have been submitted [to Indiepocalypse]. They have MS Paint art and they play poorly, but [the authors are] just trying to make, like, Mario or something, but they lack the kind of… anything… and it's weird. So I think encouraging people to make things that are not perfect, and things that are “bad art,” is good.

Alex: Right… and I think in that way too, it really enables people to really focus on the one thing they want to make good, and really deliver on that, instead of just trying to – instead of just playing some AAA game and being like, “Oh! I want to create that!” without really understanding each component.

Andrew: Right, it lets people make things that they want to make, their own self-indulgent garbage. People should do more videogame sketching, you know?

Alex: Yeah. That's really important.

Andrew: Like, here's an idea I crapped out, and it doesn't work. Maybe something out of it informs something I do later.

Alex: Yeah, I think that's the thing too, when you're learning how to design games, is that, especially when it comes to design itself, that, for one thing, finishing games in itself is a skill that needs to be learned and understood, and of course the way to learn how to finish a lot of things is to start a lot of things. There's also an extent to which, when it comes to design, that usually, you figure out what works and what doesn't in the first week or month of working on something, and then you're stuck with those choices, and you really don't get to learn from them anymore. You've walked into your mistakes, and I think you can just grow so much faster if you just make twenty shit games, and then you're like, “okay, now I really understand how not to makes these twenty mistakes” instead of just learning how to not make this one mistake.

Andrew: Games feel like they're the only art form that doesn't have that practice you see off to the side. Every other artist is clearly not just spending their whole time making the one thing. They're doing a lot of practice or just a lot of noodling around on unrelated projects.

Alex: Yeah, and I'm thinking a lot too about my experience in college, where even though I went to school for and left undergrad with a degree in political science, along the way, I had an identity crisis, and I was like, “maybe I should pick up [a second major in game development].” So at the time (some context, 2011 to 2015 was when I was in college), we didn't just have a straightforward games major, it was a games and animation major, they had combined the two, and it was a relatively small, relatively new program, with not too many professors handling the games part, and I get the impression that they really don't emphasize the sketching and the iteration in the way that you do with other art forms, like when I've taken up art classes, or learned music, or whatever. We had one design class, one “here's-how-you-make-a-game” class, and then you just have these two capstone projects, basically. And so you've come from school and you've only made two games, which is cool and good, but, you know, it's weird. Most of the games that we made weren't very good because it's literally only your first and second game.

You wouldn't do that with visual art. “Here's my first and second drawing!” You did it with crayon when you were four. And this isn't to say that good art doesn't come out of that – there are a lot of student projects that grow into really wonderful stuff.

Andrew: But I'm sure that those students are also doing a lot of other stuff in the background, in their personal time.

Alex: Right! Exactly.

[...]

On Tools, Large Solo Projects, and Danger Zone Friends

Andrew: I assume – I couldn't remember from the store page – but I feel like you primarily work in RPG Maker. Am I correct in saying such?

Alex: Not primarily, actually. Danger Zone Friends is the only complete game that I've made in RPG Maker. Actually, I use Game Maker: Studio for almost everything. I started using Game Maker when I was 12, and it just gets the job done, even though it's sadly gotten more expensive since then...

Andrew: As a fellow Gamer Maker maker/user… if you're not making 3D, why not [use it]?

Alex: - even though I've also made two [correction: three] 3D games in Game Maker, which is a pain in the ass! I don't recommend it, learn Unity unless your heart's really set on it.

Andrew: But if you're making an RPG, RPG Maker gets a lot of the busywork out of the way for you.

Alex: Right, and that's the kind of thing where I just, for the longest time… okay, back to the life story…

Andrew: Yes.

Alex: Having started publishing – heh, “publishing” - you know, sharing games by the late aughts, it was sort of the time when the indie scene was growing up, and I was encountering all of these large freeware games that are made by 1-2 people, so, you know, the Cave Stories, and the Ijis, the OFFs, and games like that. I aspired to be like, “that's what I should do. One day, I'm going to make this, spend a couple years to make this big multi-hour long game by myself and create this masterwork,” and I tried that about two or three times, and it's a terrible idea! Especially when we talk about the examples I brought up, I mean… emphasis on the “1-2 people.” Most of those successful projects required that second person!

Part of the problem wasn't so much just time and energy, but also I was just, again, talking about what we were talking about before about iteration... I was outgrowing my projects very quickly, improving as a game designer every 3-6 months, and here I was working on this project that was going to take years, and it's just like, “I don't want to work on this anymore! It's crap! I'm better than this now.”

So it was the kind of thing where, when it came to Danger Zone Friends, I had for the most part given up on the dream of making anything that was relatively large, and then one day my partner just asked me, “hey, why don't you make a game for my birthday?” And I was like, “cool, what do you want in it?” And she was like, “[I want] cute animals in it” and I was like, “okay.” She was playing a lot of RPG's at the time, she played a lot of Pokemon and had just beaten Persona 5, so I was like, okay, this is a genre that she's familiar with. So I had gotten RPG Maker in a bundle forever ago. Let's boot it up again, and lo and behold, I made a relatively large- I made an RPG!

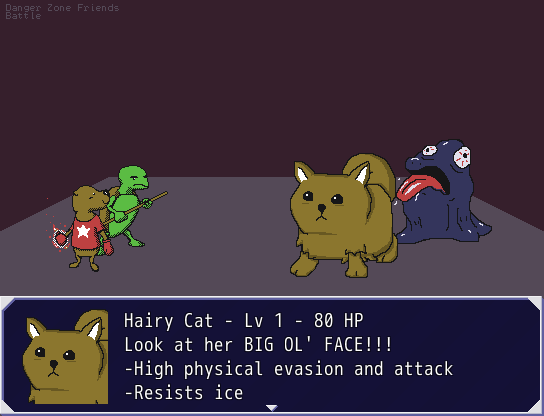

Danger Zone Friends

It's the kind of thing where part of me, for a while, did feel a little bit of shame about the fact that this is one of the few games that I did very little technical programming for. The programming languages I was familiar with were, you know, the GML/Javascript/C kind of thing, and with Ruby, the syntax is just, if you're familiar with those other kind of languages, it's gibberish, and I wasn't going to learn a whole new language for one game.

[…]

At first I felt a little shame: “it's just an RPG Maker game,” but it's the kind of thing where if it weren't for this tool, I wouldn't be able to tell this story and make this game at all, and I think it's really cool that this technology is available. Even if the menu system is identical to literally thousands of other games that exist, that's not what people remember it for, hopefully!

Andrew: Alex, let me tell you, as someone who plays a lot of “just RPG Maker” games, there's a lot of really bad RPG Maker games.

Alex: That's also true.

Andrew: Your game does not feel like an “RPG Maker game.” Your game is a game made in RPG Maker, not an RPG Maker game. I think that's an important distinction sometimes!

Alex: I appreciate that. Thank you!

On Sentimentality and Soulfulness in Games

[Andrew returns to the point that Danger Zone Friends was originally created as a birthday gift.]

Alex: Yeah! I didn't expect it to – I did not set out to create something as good as it is, but that's what I ended up with, and I was like, “I guess this is what I'm going to make people play now!” There's a little bit of awkwardness there, where having the dedication to my partner at the start and the credits is a little awkward for the thing I've made that's been downloaded more often than anything else, but it's also what makes it special. It's the whole point, and the game wouldn't be as good if it didn't come from that personal place. I don't think the characters would feel as real. I don't think that I would have as much material to work with for the jokes.

Danger Zone Friends

Andrew: Listen, Alex, if you can' enjoy your self-indulgent art, why would anybody else?

Alex: Sure! Right.

Andrew: I think a lot comes from realizing that someone enjoys what they're doing. I think you can feel that sometimes.

Alex: Yeah, there's definitely that feeling when you can tell that the person who wrote the characters in the story love the characters as much as you do as the audience member.

Andrew: There's a lot of games that I play where I don't feel any life within them. It feels like somebody's making a game to make a game for a game's sake.

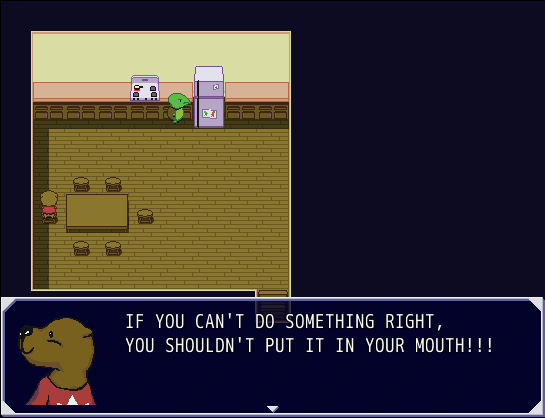

Alex: Yeah, and [it's most prevalent] when the source of inspiration is other games themselves. Thinking back to some of the very first games I made in middle school, basically, most of them were shooter games where you played as a dude who shot other dudes because that's what I was playing. They're cute in that sort of doodle way, and there's some kind of interesting things here and there, like some of the boss designs I drew when I was a kid were kind of interesting in the way that kids' drawings are, but they definitely feel kind of soulless, 'cause they weren't coming from, at least not entirely, somewhere personal. It's impossible for art to be totally impersonal, but it's not [personal in the same way as] the stuff I make as an adult.

[...]

Andrew: Do you remember the name of any of those games or the names of any characters from those childhood games?

Alex: I do. So, some of the earliest ones, and actually, they're on my old website still... the first game, well not the very first, but the first one that I shared with my friends at school, was called Blasterman. You played as a gray astronaut with a gun. You shot red astronauts with a gun. There were four of them – I mean, each one took maybe 15 minutes to get through, but -

Andrew: But that's a series!

Alex: - but yeah, that was a series! And there's this implied story where – I mean, the first one, you're just going around killing dudes, and in the second one, there's a secret boss where there's this bad guy with green armor and a sword, and he's the mastermind in the third game, it's implied, and he's the secret boss there too, but then you finally beat him in the fourth one.

Blasterman 4: Revolution

Andrew: If I'm being honest with you, I love this. It's like, perfect child story logic. It has all the drama it should have, you know?

Alex: Yeah, but it's kind of thing where, just like with a kid relaying a story to adults, nobody else playing would understand that…

[Sometime after this point, my individual segment ends, and I join Adrian, Phoebe, and Andrew for the group segment, although almost all of the following excerpts continue to be exchanges between Andrew and myself.]

Andrew: Alex, I've got to ask: what thing in a game brings you joy?

Alex: ...it's a tough question. What occurred to me is that joy is such a rare emotion to encounter in games. Games are of course very good at providing stimulation and stress and stuff like that. When I think about the games that had the moments that bring me joy, it tends to be the kind of stuff that… it's mostly through humor, I think.

[The conversation about humor in games eventually turns to the topic of the game Earthbound.]

Alex: I still need to play Earthbound before I die.

Andrew: It's a good video game.

Alex: Especially since people tell me that some of my games are kind of Earthbound-y. It's like, “I'll take your word for it,” you know? I'm sure I've gotten that influence secondhand. The stuff that I play that influences my work has probably been influenced by Earthbound. I can see the genealogy. I should honor my roots.

On Showcasing Games and Getting Games out of Game Spaces

[The conversation eventually turns to the topic of showcasing multiple indie games at a single table at a convention.]

Andrew: … That was my initial idea [for Indiepocalypse]. How do you demo 150 games? You don't. You just give them a magazine and tell them to flip through it.

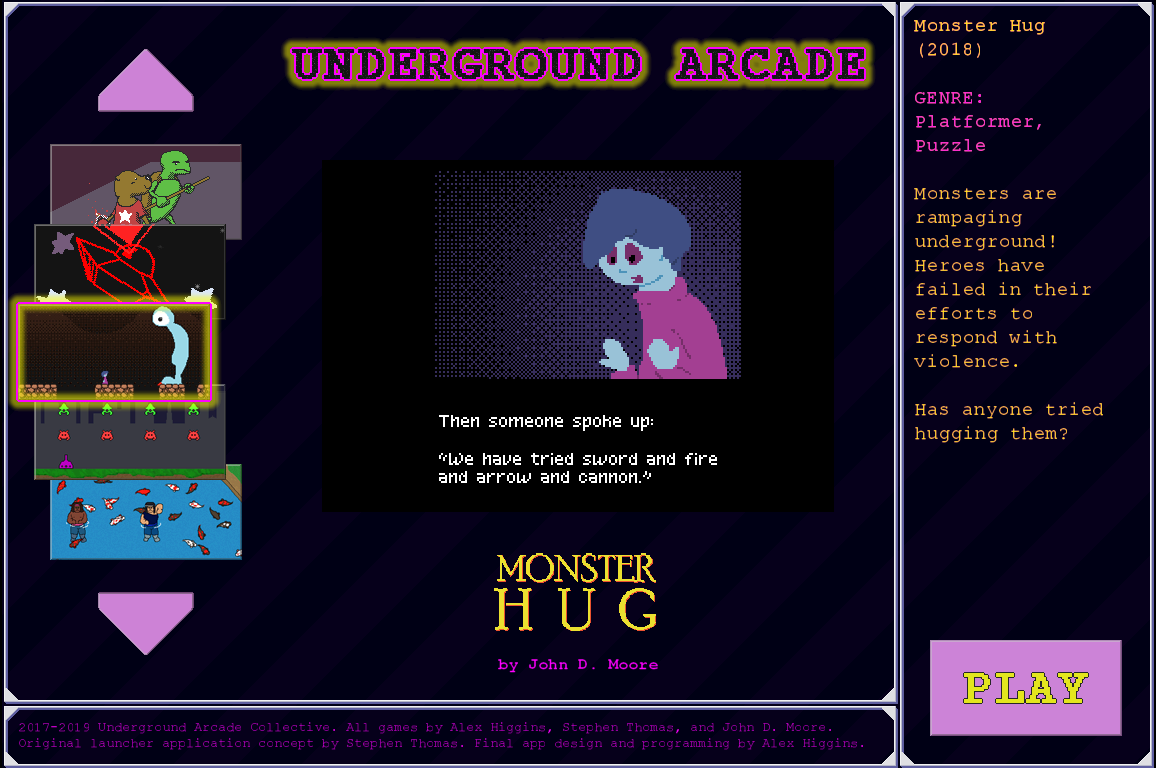

Alex: That's kind of funny. So the showcase group that we do - so what I was talking about before - my friend Stephen and I, the two of us and later our friend John D. Moore, we used to showcase, and hopefully will again someday, at local conventions and festivals and stuff in the Mid-Atlantic, in Baltimore and Philly and around there. I think the most we would cram onto our little launcher program we'd make, at our table, would be 15 games. We figured out once we exceed that that it was too many games to have demoable at the table! And honestly 15 might be a bit much, I think that 12 really is the sweet spot, but we [do] have a concrete answer to that question: how many games is too many to demo?

[…]

At our tables, we'd distribute disks that have the 15 games we're showcasing and then some more that we made. When I had some surplus disks, I'd try to drop them off at coffee shop tables, where people leave their business cards. But it's hard to find institutions where there's horizontal space where I'm allowed to just drop a CD off.

The Underground Arcade launcher program from which festival goers would choose which of our 15 games to play

Andrew: That's definitely such a thing that you should do. Get games outside of games spaces, because I'm sure plenty of those games on that disk, people would be like, “ah, I don't like video games!” And then you're like, “try this disk,” and they'd be like, “Oh! I thought video games were all like Fortnite.” It turns out there's other things too.

Alex (jokingly): There's also Minecraft, yeah!

Andrew: Yeah, there's also Minecraft! I think there's a lot of room for people to grow the games scene, which is what I'm trying to do with non-game artists for covers [for Indiepocalypse] and secret projects.

Alex: It's the kind of thing where, just because it's so rare to explore games outside of the pre-created community spaces, it's kinda hard to imagine [doing] that, and as soon as you actually explore out there, then you get all of your engagement. Returning to the topic of showcasing, after having for years released games online and not getting a whole lot of hits, it's kind of wild: I can just apply to these small conventions, and they'll just accept us? And we get hundreds of people playing our stuff? It feels like, “what the hell?”

I've had this idea of, whenever I release a game, of printing an ad out and putting it on a light pole the same way that people do for concerts and local shows and everything. Like, why not? “But wouldn't that be kind of weird, because nobody does that?” And so I've never done it because nobody does that... but that's kind of the point!

Andrew: The pull tab is just a QR code for the itch page!

Alex: Right! Yeah.

Andrew: Nothing is stopping you, Alex… When you did these showcases, did you do them at game conventions, or conventions that had game stuff, or would you just do them literally anywhere?

Alex: It was a mixture. We started at Artscape… Artscape is great. It's a big free arts festival that's in Baltimore every summer… and they have a small games exhibition. That's how we got the idea to start showcasing. So we started at Artscape, and that would usually be our main event. It was three days long, and lot of the local Maryland devs would show up every year. And it's really cool because Baltimore didn't otherwise have a standalone local games scene [outside of IGDA]. Philly does, which is one of the cool things about being here, but that's a different topic. So we do that, and there was a nerd convention in Northern Maryland, at Cecil College. [It] was a one day thing that was this community college throwing its own little con...

One time we just showcased by ourselves at a meadworks in Baltimore – Charm City Meadworks – and almost nobody showed up to that, but it was still really chill, and it was a really interesting space. We put our laptops on barrels... That was cool.

Looking at the photo evidence, I now see that I misremembered - we did not put our laptops on barrels, but we were loaned a barrel nonetheless.

In Philly there's probably our favorite event, or one of our favorites - I think Artscape is my favorite - but second [favorite] is in this printing space. It's an evening showcase where you show up at five and it goes until midnight or whatever, and it's just cramped, it's a party, it's the kind of environment I normally wouldn't like, but the vibe's very good and it's different from the typical nerd culture you get at these sort of things.

I think that the general trend is that the best events are those which aren't explicitly gamer events. Artscape's great because it's a general arts festival. The thing we do in Philly is just a bit hipper than [what is] typical. Probably our – I probably shouldn't badmouth a specific event on air – but there's one convention that's specifically a nerd convention for children, and that was a kinda weird thing where, at every other event we've done, people of all ages would play our games, but as soon as it's a kid's convention, we'd have a very similar lineup, but the adults would stand back, and only little kids would come up and play our stuff. And it's like, “you want to come up and try this too?” and they're like, “oh, no, no, we're good,” you know?

Andrew: “We don't play 'video games.'”

Alex: Yeah, bullshit, I know you do! But that one [event] was just weird.

Andrew: I often dread having – like, nothing against children – but sometimes I make abstract games, and kids can have fun with them, but they don't get the point, they're just having fun because a person's moving across the screen. “Good for you, kid,” I guess...

Alex: Sometimes there's just one really precocious kid who'll be at your booth for an hour, and they're really breaking all the systems down in whatever game, and really getting deep into it or really trying to understand it.

Andrew: I had that in TCAF at Toronto, and there was one kid who was like, yes, she understood what was going on, she was like, “yeah, I like this, it's very cool” and was asking questions, but that's also a very different vibe, cause even if it's a comic show, it's not a Comic Con. It's like an indie comics show…

Alex: And usually if a venue's bringing the kind of adult audience you want, then the kids that they're bringing with them are also the kind of child audience you want.

Adrian: I admire you guys being able to go out there and do this for so long and all that. I think it's very cool. I just want to say that... I think it's very cool to be able to go to conventions and give people the opportunity to communicate with each other, build communities…

Alex: … It's the kind of thing where until you've started showcasing, it seems like an impossible, insurmountable thing that's like, “oh, that's something that other people do.” And then you just start applying, and people just start accepting you, because, generally, unless it's a really large convention, like MAGFest is one of the few conventions we've actually gotten [waitlisted] from, and there's this whole story there -

Andrew: Good luck on MAGFest! You outlived them! Or did they come back? I don't remember…

Alex: I don't know. We'll see. But it's also the kind of thing where once we started doing it, I guess we – it's hard to imagine being welcome in a space like that until you do it, and then you figure out, “yeah, we fit in...” So, if [showcasing at local events] sounds cool to you: apply!

[...]

On Current Endeavors

Andrew: Plugs! Let's talk about plugs.

Adrian: Wow.

Andrew: Alex, let's start with you. What plugs have you got?

Alex: So, as a grad student, I am working very, very slowly on games. I'm at the stage where I'm very lucky if I have an hour or two to work on something in a one-to-two week period...

Andrew: Surely you've made games that already exist that are also still good?

Alex: Yeah, well there's that too! So I am still working on a Danger Zone Friends sequel, so that will exist someday. I have an hour and a half worth of content in there right now, and it is very cool. Let's see, other stuff… I mean, Danger Zone Friends is very good, and I also made a single-player trading card game last year called Card Games versus Literary Characters at the End of the World... if you want the physical cards, you can buy them from the Game Crafter, but, uh, only if you like the video game version.

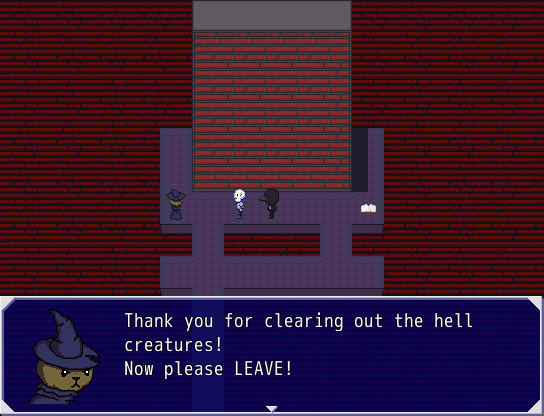

Danger Zone Friends II: Interzonal Jailbird Jam

Andrew: And where might one find all these creations?

Alex: OH! That's a great question, Andrew! You can find them at alexandrah.neocities.org, and you can also find them on my itch page. I'm alchiggins on itch.

[...]